The color of glass depends not only on the coloring agents added but also on how we adjust the valence states of elements through melting temperature and flame properties to achieve different hues. For example, copper in glass produces a blue-green hue when present as high-valence copper oxide, and a red hue when in the form of low-valence cuprous oxide (Cu₂O). Sometimes, a single melting process isn’t enough to bring out the color—requiring a second heating. A prime example is the prestigious cranberry glass, made by adding trace amounts of gold to ordinary glass ingredients during firing.

In the vast family of glass, beyond the common colorless and transparent glass we use daily, there exists a wide array of colored glass types. There’s black glass, like the violet-black glass used in car windows, and blue architectural glass. At traffic intersections, traffic lights rely on red, yellow, and green glass lenses; festive evenings are adorned with colorful light bulbs (often made from tinted glass); professional photography requires color filters over camera lenses, available in shades of yellow, red, blue, and green; drivers, field workers, steelworkers, and welders depend on tinted protective goggles; a dramatic theater performance would lose much of its impact without vibrant stage lighting; and a dynamic dance hall would feel flat without swirling laser lights in various hues.

So how do these beautiful glass colors come about?

Ordinary glass is made by melting quartz sand, soda ash, and limestone together. It is a silicate mixture with a non-fixed composition. The earliest glass produced was opaque, tinted small pieces, whose color was unintentional—caused by impure raw materials and accidental impurities. Back then, colored glass was merely decorative, with low quality standards, and produced only by chance. Today, however, colored glass demands precise scientific understanding, which we can only achieve by unlocking the secrets of glass coloring.

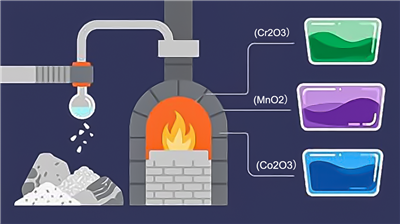

Research has shown that adding 0.4 to 0.7% of coloring agents to ordinary glass ingredients can impart color. Most coloring agents are metal oxides. As each metal element has a unique “spectral characteristic,” different metal oxides produce distinct colors. For instance:

- Adding chromium oxide (Cr₂O₃) creates green glass.

- Manganese dioxide (MnO₂) results in purple glass.

- Cobalt oxide (Co₂O₃) produces blue glass, which is used to make protective goggles for steelworkers and welders.

In fact, glass color is not solely determined by coloring agents. We also adjust element valence states through melting temperature and flame properties to alter hues. As mentioned earlier, copper in glass creates blue-green as copper oxide and red as cuprous oxide (Cu₂O). Some colors require a second heating to appear—like cranberry glass, made with trace gold. After the first melting, gold atoms disperse invisibly in the glass; reheating near its softening temperature causes the gold atoms to form colloidal particles, revealing the stunning red hue.

Today, we use rare earth element oxides to create high-end colored glass. These glasses boast pure, bright colors and can even change hue under different lighting. For example, neodymium oxide glass appears reddish-purple in sunlight and blue-purple under fluorescent light. A special type of glass changes color with light intensity, used for eyeglass lenses and window panes. Acting as a “self-adjusting curtain,” it maintains indoor brightness without needing traditional curtains while blocking UV rays—making it ideal for libraries and museums to protect books and artifacts from UV damage.

Beyond rare earth elements, adding tungsten or platinum directly to glass can also produce photochromic glass.

Post time: Jan-12-2026